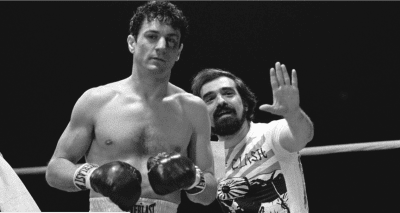

Supreme Court to Review “Raging Bull” Case

by Mark Litwak on November 12, 2013 in Film/ Movie Development

The U.S. Supreme Court has granted a petition for certiorari and agreed to hear an appeal about a copyright dispute concerning the 1980 Oscar-winning boxing film “Raging Bull.” The case was one of eight cases out of more than 2,000 pending appeals that the Court elected to accept for argument at the start of its new term. The case has implication for screenwriters and filmmakers who delay enforcing their rights against networks and studios. If the lower court decisions are upheld, judges may deny a remedy to a copyright owner even if the statute of limitations does not bar enforcement of the claim.

Frank Petrella collaborated with boxer Jake LaMotta on a book and several screenplays that were the basis for the movie “Raging Bull.” In 1976, they assigned the rights to these works to Chartoff-Winkler Productions. United Artists and MGM later acquired the motion picture rights.

In 1981, Frank Petrella died and his daughter Paula inherited his rights including his right to renew his copyrights. At the time when he created the works, copyright law provided for an initial term of 28 years of protection which could be renewed for an additional term of 28 years. Renewal registration within strict time limits was required to extend the copyright.

For many years, it was not clear if this renewal right could be assigned before the initial term expired and before it had been exercised. In 1990, the Supreme Court in Stewart v. Abend, often referred to as the “Rear Window” case, held that such an assignment was not valid when the author dies prior to the time that his renewal rights vest. This creates a potential problem for the owner of a film based on a copyrighted book still in its initial term. If the right to adapt the book into a film expires, the film owner cannot continue to distribute the film if the renewal rights cannot be secured from the person who succeeds to the author’s renewal rights.

The “Rear Window” decision was modified in 1992 by an amendment to Copyright law that limits the aforementioned rule when a claimant to the renewal rights fails to timely apply to register the renewal rights, or if the renewal registration fails to issue. In such cases, a film producer could continue to use the author’s underlying work in the producer’s film, but may not prepare new works such as a sequel based on it.

Here, the plaintiff waited until 2009 to sue MGM alleging copyright infringement, claiming she had renewed the copyright to her father’s work after its initial 28-year term expired in 1991. The defendants claim she delayed too long in bringing a suit over the renewal of his copyright and should be barred under the doctrine of laches.

Copyright law has a three-year statute of limitations, but it can renew every time another infringement of the owner’s rights occurs. However, under the doctrine of laches, suits can be barred if the plaintiff unreasonably delays initiatinga suit. As the Ninth Circuit has explained,”Laches is an equitable defense that prevents a plaintiff, who with full knowledge of the facts, acquiesces in a transaction and sleeps upon his rights.”

Courts review the reasons for the delay in deciding whether to apply the doctrine. A delay may be excused when it is required by the exhaustion of remedies through the administrative process, when it is used to appraise and prepare a complicated claim, or when the delay is to assess whether the infringement will justify the cost of bringing suit. On the other hand, a delay is generally not allowed when its purpose is to simply benefit from the delay by allowing the infringer to continue exploiting the work. In this case, a federal judge in Los Angeles and the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the plaintiff’s claim on the grounds that she had waited too long to bring a suit.

So, the question the Supreme Court has to decide is whether a statute enacted by Congress should prevail over the equitable doctrine of laches, which is determined by the court based on the facts before it. Although the plaintiff delayed 18 years in bringing her suit, that suit was preceded by a series of letters threatening litigation by her attorneys beginning in 1998.

The plaintiff contends that “Laches requires a variable, fact-specific balancing of the equities, whereas the statute prescribes a predictable bright-line rule. The Ninth Circuit’s rule not only is legally erroneous but also threatens to breed forum shopping – the very evil Congress sought to prevent when it enacted a uniform statute of limitations.”Other circuits have rejected the laches defense and allowed copyright cases to proceed as long as the plaintiff’s case has been filed within the statute of limitations.

However, in a concurring opinion Judge William A. Fletcher for the Court of Appeals noted that “Our circuit is the most hostile to copyright owners of all the circuits.” Indeed, the Ninth Circuit has a reputation for protecting the Hollywood studios against copyright claims.

A group of entertainment lawyers have filed an amicus brief claiming that “the Ninth Circuit systematically erects more hurdles to copyright plaintiffs than do many other Circuits, all but immunizing motion picture studios and television networks from infringement claims.”

In a 2010 Los Angeles Lawyer article titled “Death of Copyright,” attorney Steven T. Lowe, argues that of the 48 copyright infringement cases against studios or networks that resulted in a final judgment within the Second and Ninth Circuits (and the district courts within those circuits) in the last two decades, the studios and networks prevailed in all of them and nearly always on motions for summary judgment.[1] A follow up article in 2012 identified another five cases decided by the Ninth Circuit in which the studio or network prevailed.

Consequently, the Supreme Court’s decision could affect the ability of plaintiffs to successfully sue the studios and networks for copyright infringement.

[1]Lowe, Steven T., Death of Copyright, Los Angeles Lawyer, November 2010, http://www.loweandassociatespc.com/press/publications/death-of-copyright.